10 Gennaio 1989 A Deakin – Canberra (Australia) ucciso Colin Winchester, vicecapo della polizia federale.

Colin Winchester è stato il vicecapo della polizia federale, assassinato a Canberra il 10 gennaio del 1989 con due colpi di revolver alla testa. Rosario Zerilli viene indicato come l’esecutore materiale del delitto. Il superpoliziotto stava indagando su terreni acquistati dalle famiglie della Locride con i soldi provenienti da alcuni rapimenti in Lombardia nei quali erano rimasti implicati esponenti dei Perre, dei Sergi, dei Papalia, dei Barbaro, tutti originari di Platì, la cittadina calabrese che deteneva “il record assoluto dell’emigrazione italiana in Australia”. Negli anni Ottanta, l’Abci, l’anticrimine australiana, accertò l’esistenza di una struttura criminale estesa su tutto il territorio, dedita prevalentemente al traffico di droga. L’organizzazione era dominata da capi bastone: Giuseppe Carbone (Australia meridionale con l’eccezione di Sydney), Domenico Alvaro (Nuovo Galles del Sud, con l’eccezione di Griffith e Canberra), Pasquale Alvaro a Canberra, Peter Callipari a Griffith, Pasquale Barbaro a Melbourne e Giuseppe Alvaro ad Adelaide.

Tratto da: Fratelli di Sangue di Nicola Gratteri e Antonio Nicaso

Fonte: en.wikipedia.org

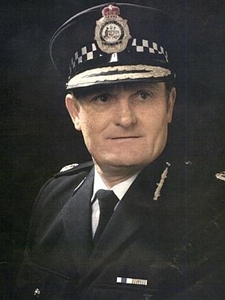

Colin Stanley Winchester APM (18 October 1933 – 10 January 1989[2]) was an assistant commissioner in the Australian Federal Police (AFP). Winchester commanded ACT Police, the community policing component of the AFP responsible for the Australian Capital Territory.

Background

Winchester, the son of a baker, worked as a miner near Captains Flat before joining the Australian Capital Territory Police Force in 1962, aged 29 years. The ACT Police and Commonwealth Police were merged in 1979 to form the Australian Federal Police (AFP).

Death

On 10 January 1989, at about 9:15 pm, Winchester was shot twice in the head with a Ruger 10/22 .22-calibre semi-automatic rifle fitted with a silencer and killed as he parked his car in the driveway of his neighbour’s premises in Deakin, Canberra. Winchester is Australia’s most senior police officer to have been murdered. At the time of Winchester’s murder, it was alleged that Winchester was corrupt, at any earlier period when it was said that he had handled bribes relating to a Canberra illegal casino. However, an audit of Winchester’s financial affairs after his murder revealed nothing untoward. There were also allegations of ‘Ndrangheta or mafia involvement in his murder. The story of Winchester’s murder was dramatised in Police Crop: The Winchester Conspiracy.

Conviction and subsequent quash of conviction

Prior to Winchester’s murder, David Harold Eastman, a 44-year-old former Treasury Department economist, had made threats against Winchester’s life.

In 1995 Eastman was tried and convicted of the murder of Winchester and was sentenced to life imprisonment without parole. During the 85-day trial, Eastman repeatedly sacked his legal team and eventually chose to represent himself. Eastman also abused the judge during his trial, and during later legal proceedings and appeals. Subsequent to his conviction, Eastman continuously appealed against his conviction, attempting to win a retrial on the basis that he was mentally unfit during his original trial. On 27 May 2009, Eastman was transferred from the Goulburn Correctional Centre in New South Wales to the ACT’s Alexander Maconochie Centre to see out his sentence.

A new inquiry relating to his conviction was announced in August 2012. In 2014, the inquiry, headed by Justice Brian Ross Martin, found there had been “a substantial miscarriage of justice”, Eastman “did not receive a fair trial”, the forensic evidence on which the conviction was based was “deeply flawed” and recommended the conviction be quashed. However Martin said he was “fairly certain” Eastman was guilty but “a nagging doubt remains”.

In 2016 it was reported that the ACT Government sought a retrial of Eastman over the murder of Winchester; and that the legal precedings had cost the ACT Government approximately A$30 million. Meanwhile, Eastman lodged a civil claim against the ACT Government seeking compensation for wrongful imprisonment; and on 14 October 2019 Eastman was awarded A$7.02 million in compensation.

On 22 November 2018, Eastman was found not guilty of Winchester’s murder after a lengthy retrial.

Legacy

Following his murder the Winchester Police Centre, located in Benjamin Way, Belconnen, was established in 1994 as the headquarters for ACT Police. The Winchester Police Centre houses ACT Police Executive, administrative and support sections and elements of the Territory Investigations Group (TIG).

Fonte: citv.com.au

The highest ranking police officer in Australia to be murdered, Assistant Federal Police Commissioner Colin Winchester was shot twice in the head at point blank range as he was getting out of his car outside his Deakin home on January 10, 1989. At the time of his death Winchester was the Chief of Police in ACT region. He had served in the law enforcement of 27 years, firstly with the Australian Capital Territory Police Force and then in the Australian Federal Police after its formation in 1979. The shock of his death and the long investigation which followed left a lasting imprint on his fellow officers as they struggled to bring the killer to justice.

Articolo dell’11 Novembre 2013 da heraldsun.com.au

The man convicted of murdering top cop Colin Winchester could be freed amid claims the mafia were behind the assassination

CONVICTED cop killer David Eastman could be freed after having serving 18 years of a life sentence for a crime he claims he didn’t commit.

Eastman hopes a judicial inquiry – which began hearing evidence in Canberra on Cup Day – will clear his name.

The former public servant is pinning his hopes on his claim there is evidence it was the Calabrian mafia that shot dead Australian Federal Police assistant commissioner Colin Winchester in 1989.

Police will be arguing at the judicial inquiry, which is expected to run for several months, that the “mafia did it” angle was fully investigated and ruled out, and that they got the right man: Eastman.

Mr Winchester, 55, is the most senior public official ever assassinated in Australia.

There were no witnesses to the two quick shots that killed him, and the Ruger 10/12 self-loading rifle used in the slaying was never found.

The Winchester execution made headlines around the world almost 25 years ago.

And the judicial inquiry, which Eastman won by successfully arguing before the Australian Capital Territory Supreme Court that there was new evidence casting doubt on his conviction, has now put it back in the news again.

Mr Winchester probably never knew what hit him as he prepared to get out of his cream Ford Falcon about 9.15pm on January 10, 1989.

He had just driven the unmarked police car into the driveway next door to his home in Lawley St, in the Canberra suburb of Deakin. He had an arrangement with his neighbour, an elderly widow, to park his car there to offer her some sense of security.

The waiting assassin had the cover of darkness, as well as the shelter of tall gums and shrubs, as he watched Mr Winchester’s car slow and stop, before creeping up from behind.

Bringing his .22 Ruger rifle to his shoulder, he waited for the father of two to open the car door and start getting out.

The first shot was fired into the back of Mr Winchester’s head from a distance of 40 to 60cm.

A second was fired into the side of the head, just above the right ear.

An autopsy later revealed either shot would have been fatal.

The killer fled without being spotted, and left nothing behind that might have identified him.

Two shell cases were unsuccessfully tested for fingerprints.

Gwen Winchester had heard the car arrive and within seconds heard what she described as two sharp cracks, separated by half a second or so, which sounded like “sharp stones coming up on to the front of the window”.

She went outside to investigate and saw her husband’s car parked in its usual spot. She noticed the interior light was on, that the driver’s side door was open, and that her husband was still seated in the driver’s seat, his right foot on the ground.

He did not respond to her shaking and appeared unconscious, so she ran back inside and rang 000, saying she thought her husband had had a heart attack.

Frantically rushing back outside, she put her hands behind his head to start mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, felt wetness, and saw blood.

She noticed a pack of bullets on her husband’s lap and “for one crazy minute I thought he must have committed suicide”.

Mrs Winchester later learned he had picked up the ammunition for a hunting trip.

Hands covered in blood, Mrs Winchester ran back indoors to ring 000 again.

What followed became one of the highest-profile murder investigations Australia has seen.

Within three days the Federal Government announced a $250,000 reward, and offered protection to informants – including a change of identity – and possible indemnity from prosecution in return for the capture of the killer.

The then justice minister, Michael Tate, said the murder had the hallmarks of a paid execution.

Italian organised crime figures were hot suspects even before the body was cold.

Mr Winchester was a key figure in one of policing’s most controversial operations against a Calabrian mafia gang, and 11 of them were about to face trial on charges related to marijuana crops in the NSW town of Bungendore.

Some of those charged had been led to believe Mr Winchester was protecting them in return for money and felt double-crossed.

But Mr Winchester had actually been working with police informer Giuseppe Verduci to try to penetrate the gang.

That association with Mr Verduci led many police to presume members of the Australian-based Calabrian mafia, which was responsible for ordering the death of Griffith anti-drugs crusader Donald Mackay in 1977, were also responsible for this murder.

Information passed to the National Crime Authority from police in Italy within days of the Winchester murder further convinced some police the Calabrian ‘Ndrangheta was responsible.

In interviews with the Herald Sun before the current inquiry began, Winchester murder investigation head and former AFP commander Ric Ninness said he was initially unaware a team of investigators was pursuing information provided by the Carabinieri, the Italian police, that a Calabrian crime figure had flown to Australia from Italy shortly before Mr Winchester was killed.

The Carabinieri told the AFP the crime figure was notorious for his connections to the Calabrian ‘Ndrangheta and an accomplished handler of weapons.

AFP checks revealed the crime figure had indeed travelled to Australia with another Italian born in Plati – the Calabrian city that is the world headquarters of the ‘Ndrangheta – just before the Winchester murder.

The pair were met at Melbourne airport by two uncles, both of whom had been charged over the Bungendore drug crops.

It shaped as the most promising lead in the early days of the murder investigation.

Mr Ninness said the Winchester investigation was initially split into two camps with very little co-operation: the one he headed with Commander Lloyd Worthy, and another team at AFP headquarters investigating the Italians after the Italian police tip-off to the NCA.

“There was a lot of friction,” Mr Ninness said. “There were two divided camps and it was a very bad move.

“We were the primary investigation team that was reporting to the Coroner and ultimately the courts.

“We were responsible for preparation of the evidence, and unbeknown to us there was a team set up at headquarters running off doing things that we weren’t aware of.

“I went over and had a meeting with the commissioner (Peter McAulay) and voiced my strong disappointment at what was happening, as the left hand didn’t know what the right hand was doing.”

Mr Ninness said things then improved.

“The Italians were logical suspects, and I would never refute that. But you have to get factual evidence that can go before a court and be admissible, and that never came out,” he said.

“There was never any credible evidence that came out at any stage in relation to the Italians. Every suspect was exhaustively examined, and we gradually whittled away all the also-rans until there was only one person left.”

That person was former Treasury clerk David Harold Eastman.

[…]

Eastman won the current inquiry after losing appeals in the Federal and High Courts.

ACT attorney-general Simon Corbell established the inquiry after ACT Supreme Court judge Justice Shane Marshall ruled there was fresh doubt about Eastman’s guilt that raised significant risk that the conviction was unsafe.

The inquiry will look at issues including Eastman’s fitness to plead, the accuracy of the forensic evidence, and the conduct of police and prosecutors.

It could lead to Eastman’s murder conviction being quashed without a retrial, quashed with a retrial, or a confirmation that the conviction stands.

Part of a secret police dossier that blames the Sergi Calabrian mafia cell for executing Mr Winchester was recently revealed during the Martin inquiry.

The Sergi clan was identified in the confidential document as the group probably responsible for the Winchester murder.

Several Sergis based in Griffith, New South Wales, were named by a royal commissioner in 1979 as being Calabrian mafia members.

Extracts from the police document which fingers the Sergi clan for the Winchester hit were revealed in a recent submission to the Martin inquiry by the ACT’s DPP.

Eastman is trying to convince the Martin inquiry it was the Calabrian mafia, not him, that shot Mr Winchester.

The DPP’s submission to the inquiry included a letter written by Eastman in which Eastman quotes from secret police documents which explored the possibility of the Calabrian mafia being responsible for executing Mr Winchester.

It was written by Eastman in 2005 and formed part of his plea to the ACT Supreme Court as to why there should be an inquiry into his conviction.

Eastman’s letter to the Chief Justice said the grounds for ordering an inquiry included “strong hypotheses consistent with my innocence”.

“These hypotheses concern the strong likelihood that the murder was drug-related and was committed by organised crime,” Eastman’s letter said.

“I enclose a copy of MFI-130, which is a police report which concludes in its Executive Summary that the murder was committed by the Sergi organised crime group.

“MFI-130 was not used at my trial because my barrister, Mr Terracini, did not know that it was among the many documents in his possession and I also did not know of its existence.

“I also enclose a copy of MFI-23, which is another police report, that says, in paragraph 1.5, that investigation of the organised crime leads should continue and ‘this could eventually provide information or evidence directly linked to the murder’.

“One of the detectives centrally involved in conducting those further inquiries, the late Detective Cliff Forster, told my lawyers in 1998 that those inquiries were never satisfactorily completed.

“I enclose a 3-page document recording those conversations.”

It is believed Eastman was mistakenly sent the confidential police documents during the legal discovery process while he was fighting to get the judicial inquiry.

The Herald Sun has been told later documents produced by police following further investigation discount the “mafia did it” theory.

Those documents, and the confidential MFI-130 and MFI-23 documents Eastman is relying on to try to prove his innocence, will be examined in depth in coming months by the Martin inquiry.

Sergi clan members have been murder suspects in the past.

They were accused by a royal commissioner of arranging the 1977 murder of budding politician Donald Mackay because of the effect the Griffith businessman’s public anti-drug stance was having on the Calabrian mafia’s lucrative marijuana business.

The mafia blamed Mr Mackay for tipping off police about two huge drug crops in the Griffith area. The resulting busts cost the organisation $42 million in lost marijuana sales.

So a decision was made that the troublesome Mackay had to go.

The mafia’s Mr Fix-It, Robert Trimbole, was given the job of ensuring Mr Mackay disappeared off the face of the earth.

Mr Mackay vanished on July 15, 1977, and his body has not been found.

The hitman, Melbourne painter and docker James Bazley, served time over the shooting, but Trimbole was never charged and neither was any member of the Sergi clan.

Police informer Gianfranco Tizzoni told detectives in a statement tabled in a royal commission that he attended a meeting at Tony Sergi’s Griffith winery in May 1977 where the execution of Mr Mackay, 43, was plotted.

Tizzoni said Mr Sergi – now 78 – was one of several people at the meeting and that disposing of Mr Mackay in the Calabrian style using “el lupari” – a shotgun – was discussed.

He retracted the statement two days later and made a second statement that did not implicate those he initially named.

The Griffith winery owner told the Herald Sun in 1997 he was not involved in the Mackay murder or any other crimes.

Carl Mengler, a former Victoria Police deputy commissioner and the detective who headed the Victorian investigation into the Mackay disappearance, believes Tizzoni’s first statement was the true one.

He said Tizzoni withdrew it after sitting in a cell with time to think of the possibility of retribution for having named a number of people as having conspired to murder Mr Mackay.

Mr Sergi denied to the Herald Sun in 1997 that he had attended any meeting that discussed executing Mr Mackay.

“I’m innocent. Why does my name keep coming up?” he said at his home, which is at the rear of his winery.

“I didn’t even know Mackay. I never met Tizzoni either.

“This is awful for my family, to have all this brought up again.”

Drugs royal commissioner Justice Woodward’s 1979 report described Mr Sergi as “the operator” of Griffith’s marijuana growing operation.

Justice Woodward named Mr Sergi as being a member of the Calabrian mafia.

The Woodward report also named five other Griffith-based Sergis as being members of the Calabrian mafia.

[…]

Fonte: theguardian.com

Articolo del 23 novembre 2018

Colin Winchester’s murder and how the case against David Eastman collapsed

di Christopher Knaus

The economist was convicted of the murder in 1995, had the conviction quashed in 2014, faced a retrial – and has now been found not guilty

The courtroom was eerily quiet on the day David Eastman’s murder conviction began to unravel.

It was late summer 2014 and, outside the walls of the Australian Capital Territory’s supreme court, Canberra was flooding. Torrential rain and wild storms were bringing trees crashing down on to houses, flooding schools, swelling stormwater drains and grounding flights.

But the court pressed on. The end was in sight to its almost six-month inquiry into Eastman’s 1995 conviction for the assassination of Colin Winchester – the Australian federal police assistant commissioner who commanded the ACT’s police force.

It was a crime for which Eastman had spent almost 19 years behind bars and a case that, for many years, gripped the nation.

Winchester had returned to his Deakin home late from work, about 9.15pm on 10 January 1989. As usual, the police chief parked his car outside his widowed neighbour’s home, a small gesture to make her feel safe.

Winchester’s killer waited in the darkness. Two shots were fired as he moved to get out of his car; the first to the back of his head, the second to his right temple. Inside, his wife Gwen heard noises “like sharp stones coming up on to the front of the window”.

She walked outside to find her husband slumped behind the steering wheel. Winchester remains the highest-ranking officer to be murdered in Australia’s history.

Rumours swirled about the involvement of the powerful Calabrian mafia, known as the ’Ndrangheta or honoured society, whom Winchester had double-crossed in a 1980s undercover sting that brought down their cannabis crops near Bungendore in New South Wales.

A vast, all-consuming police investigation instead shifted its focus to Eastman, a Treasury official, who was furious with police for refusing to drop an assault charge against him.

Advertisement

The public watched every step of the case.

First as Eastman was charged with murder in 1993. Then as he was convicted in 1995 and sentenced to life imprisonment. And on and on, as Eastman used every possible avenue of inquiry and appeal to free himself from prison and clear his name for a murder he said he never committed.

But on that summer afternoon in 2014, the court’s public gallery was all but deserted. National interest had long ago waned and Winchester’s murder was fading from the consciousness of most Australians.

The 2014 inquiry was poring over the forensic evidence used to tie Eastman to the murder scene. It was crucial evidence at the 1995 trial.

Gunshot residue found in Eastman’s car boot was said to be a precise match to that found at the scene of Winchester’s death.

It was lauded by prosecutors as strong and unchallenged evidence of Eastman’s guilt, and the trial judge later described the police work as “one of the most skilled, sophisticated and determined forensic investigations in the history of criminal investigations in Australia”.

The lead forensic witness, who cannot be named, was presented to the jury as completely independent, his veracity and expertise without reproach.

That all came tumbling down in a single afternoon. A secret tape, never heard before, was played through the court speakers. Lawyers glanced at one another in expectation.

The recording had been made by a detective working the Winchester murder, Thomas McQuillen. He had begun to have reservations about the case’s lead forensic investigator. So he secretly taped their conversations.

The audio betrayed any notion that the star forensic witness was impartial. It also clearly showed his fear of having others check his work.

“I’m working with you. As far as I’m concerned I’m a, I’m a crown witness, a police witness,” the supposedly independent forensic expert told McQuillen. “I’m not going to see the brief suffer.’”

Then, speaking about other forensic scientists who had reviewed the evidence and disagreed with his findings, he said: “If we don’t put a brake on these turkeys, I mean, we don’t want these bastards putting that sort of stuff in writing. They’ve got to be told, you don’t say I do not agree. You ask questions all right.”

Eastman’s defence was never told any of this.

In fact, the defence’s attempts at trial to discredit the crown’s lead forensic witness were openly and successfully ridiculed by the prosecution. Had his lawyers been told of the witness’s behaviour, Eastman’s defence may have had cause to begin questioning the forensic evidence more thoroughly.

Advertisement

Had they done that, they would have realised it was deeply flawed.

The expert had made embarrassingly basic errors. He mixed up evidence taken from Eastman’s car and the crime scene. The mix-up was slammed by the inquiry’s senior counsel assisting, Liesl Chapman SC: “For a forensic scientist, it doesn’t get any worse than that.”

He accidentally destroyed evidence, overstated his conclusions and used a deeply flawed database of ammunition types – prepared by a student – to reach the conclusion that the gunshot residue in Eastman’s boot and that at the scene were one and the same.

The inquiry found later in 2014 that: “The issue of guilt was determined on the basis of deeply flawed forensic evidence in circumstances where the applicant was denied procedural fairness in respect of a fundamental feature of the trial process concerned with disclosure by the prosecution of all relevant material.

“In addition, evidence of inadequacies and flaws in the case file and case work of the key forensic scientists were unknown to everyone involved in the investigation and trial.”

Eastman was freed late on the evening of 22 August 2014. He lay beneath a blanket in the back seat of a station wagon, hiding from the cameras as he was bundled away from the prison where he had spent the past 19 years of his life.

The inquiry head, Brian Martin, a former Northern Territory supreme court chief justice, said he was “fairly certain” of Eastman’s guilt but said he still had a “nagging doubt”. Martin recommended that Eastman not be tried again.

The ACT supreme court and local prosecutors took a different view.

Prosecutors maintained that, even without the forensics, there was plenty to prove Eastman’s guilt. He was allegedly seen scoping out the area around Winchester’s house, had a burning hatred of police and Winchester, had uttered threats and bought a gun police believed to be the murder weapon. They said the case against Eastman remained overwhelming.

This year, almost 30 years after Winchester’s death, it came back to the ACT supreme court for retrial. Jurors heard new evidence about the mafia’s possible involvement, though the evidence was taken largely in secret.

Now-ageing witnesses were brought back, again, and the crown once more tried to build a circumstantial case pointing to Eastman’s guilt. The retrial was wholly supported by the Winchester family.

Advertisement

The jury spent seven days deliberating. At one point this week, it looked as though it would not reach a verdict. But on Thursday morning the news came through. A decision had been made. Eastman was not guilty.

His legal aid lawyer, Angus Webb, said of the decision: “Justice has been done.”

Winchester’s widow, Gwen, died without any semblance of closure. She passed away several months after Eastman’s conviction was quashed and he was released. The remaining family say they are deeply disappointed with the decision. They have been subjected to speculation, rumour, innuendo and legal proceedings since Winchester was shot dead.

John Hinchey, the ACT’s former victims of crime commissioner, said police would be similarly upset. “They would be heartbroken, I would believe, and grief-stricken, again,” he told reporters outside court. “It is another day of mourning for the AFP and the Winchesters.”

Eastman himself has not spoken publicly.

For most of the 2014 inquiry, he was rumoured to be sitting in prison, quietly listening in via audiolink.

It was a notable difference from his behaviour in the 1995 trial. Then, he clashed openly with the trial judge, the prosecution and his own lawyers, whom he repeatedly sacked, only to be left self-representing during critical parts of the hearing.

“It would not be an exaggeration to describe it as chaotic,” an appeal court noted in 1997.

Eastman made “vile, foul-mouthed, vituperative comments” to the judge and prosecutor, and he was removed from the trial for a time and placed in a separate room with a two-way video link.

“His honour was able to supervise the sound control so that the volume could be turned down when the appellant’s abusive language warranted such action,” the appeal court noted.

Eastman, who has been found to suffer a paranoid personality disorder, has tried, unsuccessfully, to claim he was unfit to plead in the 1995 trial.

He said police had deliberately placed him under immense pressure during their investigation, hoping he would crack and make a confession.

The resources deployed against Eastman were vast. Police bugged his apartment and tailed him everywhere. It was deliberately overt and “in-your-face” surveillance at times, the inquiry found.

Police knew of Eastman’s personality disorder, and were advised to keep up regular contact with their suspect in the hope of tipping him over the edge.

They falsely accused him of “homosexual activities with boys” and would often knock on his door unannounced to “return property”. On one occasion officers stuck their foot in the door when Eastman tried to dismiss them.

They monitored him during him his daily swim at a Canberra pool and had a female officer sunbathe in the pool every day.

The lead detective on the case, Richard Ninness, explained the tactic. “He’d usually go to the Olympic swimming pool in Civic and we orchestrated a situation with the policewoman, she was sunbathing at the pool on a daily basis,” he said.

“He struck up a rapport with her and invited her on an outing and he took her to the war memorial and we knew in advance where they were going.”

When he returned to his car from the war memorial, police were waiting for him.

Ninness would even swim at the pool at the same time as Eastman, to keep eyes on him.

“I used to go to the swimming pool and he used to swim at the same Olympic pool … it was important that I keep some sort of visual, even though I didn’t talk to him, that he actually saw me there and my presence,” Ninness said.

Eastman frequently complained of harassment and his lawyer, Stuart Pilkington, wrote to the police to tell them his client did not want to take part in an interview.

In response, Pilkington said he had received a drunken call from Ninness.

He told the inquiry: “Detective Sergeant Ninness said words to the following effect: ‘I got your fucking letter. If I want to talk to your little cunt of a client, I’ll fucking well talk to him whenever I fucking well like. You can stick your fucking letter where it hurts most.’”

The inquiry found the strategy was deliberate and “inappropriate”, even for the attitudes accepted in the 1980s and 90s.

“The harassing and provocative conduct was undertaken with the deliberate intention of provoking the applicant into saying something incriminating, which could be recorded on listening devices in his home,” the inquiry found.

The jury’s verdict on Thursday once again leaves the Winchester case open. It means the murderer of the highest-ranking police officer in Australia’s history remains at large.